Look around you at John Bellany’s Paintings on Exhibition here (Aschaffenburg, Germany). The first impact is vivid and immediate. Colour, rapid execution, informal composition reveal that these are plainly emotional pictures, that they were painted under pressure of strong feeling. And then as you look further you begin to get a sense of narrative, too. Each picture sets a scene. Figures inhabit them, sometimes in groups, sometimes alone.

And then, too, these figures, whether human characters or strange creatures – birds, fish, dogs or something in between – and the landscapes that frame them recur from picture to picture as though not only individually, but somehow together too, these paintings are telling a story.

But if you go up to one of them, you cannot find a simple narrative key. There seems to be no straightforward interaction between the figures, no hint of the action on which any ordinary human drama would depend. In fact they are hardly dramatic at all except in appearance, in execution and often in characterisation too for the figures are frequently bizarre. But nor is there any easy logic in the relationship of internal to external space, say where a room is set against a view of a harbour. Often too, a figure in a picture within a picture, far from being inanimate and apart, seems to take part in the scene as much, or as little as the figures that are apparently ‘real’. And more often than not the exotic inhabitants of these paintings, human, fish or animal, gaze enigmatically out at you, not inwards at each other. They are interacting with you. This is not simply some internal pictorial drama. You are part of the story, if there is one.

So what is going on? What is this strange scenario where you are both spectator and part of this exotic cast? Certainly these are not simple narrative paintings. Indeed they are not structured according to the rules of pictorial story-telling at all. They are much more like dreams where people and things that are familiar assume an unfamiliar aspect and behave in illogical ways, leaving us often with a sense of an event that has taken place, but which has slipped straight into the subconscious leaving only a ripple on the surface of the conscious mind, a memory that never quite was, like the flash of a kingfisher diving and disappearing just beyond the corner of your eye. The strength of this painting lies in the way it captures this elusive, allusive quality, the nostalgia of half-remembered dreams, associations too fragile to catch but that can evoke a mood as powerfully as a long forgotten perfume.

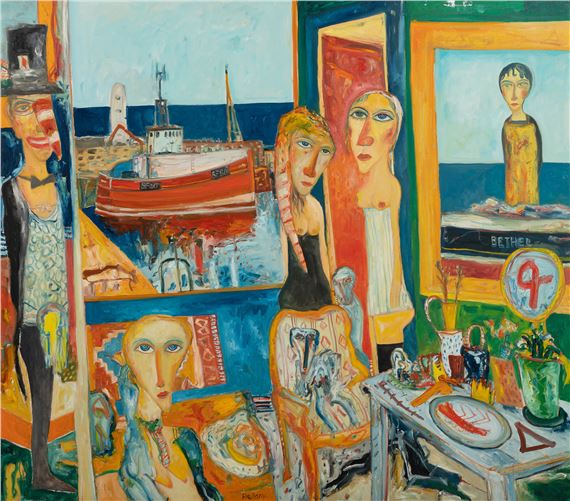

A Scottish Saturday Night seems a key image. Two women stand in an interior that opens on to a harbour. A red fishing boat moored to a pier is reflected in still water. The dark blue sea beyond draws a clear line of horizon beneath a pale blue sky. The women, or girls perhaps, are in a state of undress, naked breasts over corsets. One wears black stockings. In spite of this erotic garb, their expressions are open and innocent. But a leering, joker figure in fancy dress, a top hat and comic nose, seems to be hiding behind a door to spy on them. His sinister presence calls into question their apparent innocence. Another figure in the foreground, a child with an old-young face perhaps, looks out at us with the same innocent intensity as the girls. But a strange polymorphic creature curled up in a chair echoes the joker’s unsettling presence.

There is a table nearby laden with a variety of objects that might be domestic or might be the paints and brushes in an artist’s studio. But then above this, a painting is hanging on the wall. In it a figure stands against the sky and the sea’s blue horizon, the same horizon as we see through the window. So this picture within a picture reflects the same inside-out reality. Continuing this connection, the figure seems to be a boy in fisherman’s working clothes, an inhabitant of the working world of the harbour beyond.

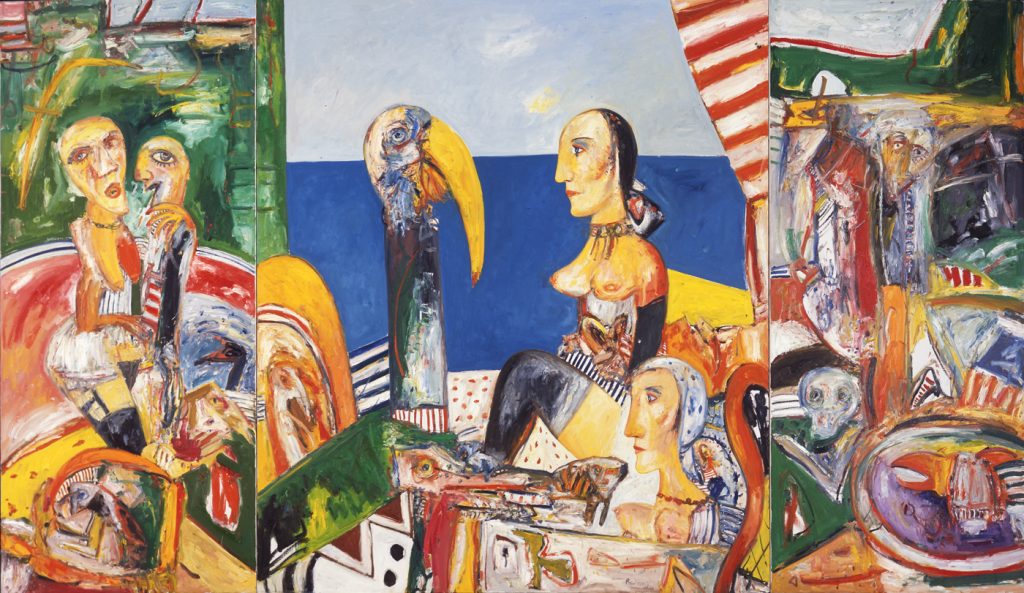

This harbour, or another like it, also with a fishing boat and a pier against the dark blue horizon, dominates the centre of A Scottish Idyll too. There is the same tense, unresolved relationship between the figures here: a mother with a baby, two girls with naked breasts, a ghostly white figure in the foreground – perhaps a real ghost, she appears in several other paintings too. Reality shifts between the framing of windows and the framing of pictures. A grotesque figure with a stork’s bill looks on sardonically. The same strange creature joins two girls in The Sisters. In A Scottish Concerto, in a bourgeois interior with a white lighthouse framed against the sea, two more girls also in a state of undress are making music while a male figure looks on.

In Vision of the Bride similar things happen. A motley crew of grotesques are gathered round a half-naked bride whose gaze this time is direct and knowing. Two birds seem to mock the bizarre behaviour of humanity from the superior point of view of nature untroubled by human angst. One of them is wearing the same joker’s comic nose. Two pictures hang on the walls here, but they could also be windows. In one a bearded man looks on, his head bandaged like Van Gogh. The other seems to be a Crucifixion. In both there is the same blue horizon. Then this wanton bride appears again in the painting called just that The Wanton Bride. Halfnaked too, her glance is self-aware and seems to offer a direct sexual challenge. But somehow the colour and the handling link this to the landscape beyond. Hills profiled against the sky, a fishing boat dark blue water, these are not just a background for she seems a part of them.

In Avail this bride, or her sibling, dominates what seems to be a more straightforward landscape of boats and harbour. And here there are more figures in the distance. A fishing boat, The Avail that gives the picture its title, is drawn up on land. Its stern hangs over the girl. But where its rudder should be, a little family group is framed by the curve of the boat. Strange creatures gather round the girl’s knees subverting the simplicity of the scene. On a boat passing in the distance four figures seem to be standing in an orderly line, strangely erect. These four appear again in the same situation, but are more clearly visible in Waiting for the Tide. In Elegy for Elspeth there are five of them.

And in A Boat Called Maria two of these watchers seem to have come ashore. Their boat, the Maria, is diminutive, but though it is pulled up on land, they are still standing in it. Belying the romantic reference to West Side Story in the title and so to the intensity of young love, they seem sexless. But the fish on the head of one of them seems nevertheless to be a surreal, sexual reference. So does the lugubrious puppylike creature with a dangling phallic nose that shares the boat – something very like it appears with a similar couple in Aberlady Bay – while here the warm colouring of the figures and their seeming defencelessness, isolated against the pale blue sea, set an intensely romantic note.

If the fishing boat that figures in so many of these paintings comes ashore here with its strange, romantic crew, the harbour itself is the subject of two brilliant, direct landscapes that might have been painted on the spot. They are both of the fishing village of Port Seton in East Lothian, scene of the artist’s boyhood. One, Port Seton Harbour, is a view of the harbour looking out across a row of fishing boats eastwards down the Firth of Forth to North Berwick Law, a conical volcanic hill that guards the entrance to the Firth and a landmark visible for many miles. The other, Port Seton Sunlight, is the view inland from the pier towards the village: red East Lothian stone, brightly painted fishing boats and houses, blue sky.

Such straightforward landscapes are rare in Bellany’s exhibited works, but they play a key role in the collection shown here. The light and colour in them is echoed in all these paintings in just the same way as the scenery. And the sun that shines in them, that gives its title to the second one, Port Seton Sunlight, surely has the strange brilliance that memory distils from the sunshine of the distant summer days of childhood. And so they give us a clue to the way these pictures are about memory. All painted in the last year or so they may not constitute a retrospective in the conventional sense, but together they do seem to look back over the artist’s life, to explore scenes and memories of childhood and adolescence and to meditate on iconography that has evolved from his troubled experience reflected in nearly forty years of painting.

Just as it was the scenes of his boyhood by the river Stour, the locks and the barges of that river highway and the life around them, that by his own declaration shaped Constable’s art, so the fishing boats and the harbour of Port Seton and the fishing community that focused on them are the things that have made Bellany an artist from the start. When he was still at school, a precocious artist he was already winning prizes for art whose images reflected that world directly. But if for a child its environment is the whole universe, the trick that an adult artist must pull whose art is rooted in that childhood world is to realise its true universality, to scale up that experience so that it can stand as metaphor accessible to all of us for the wider world we share.

In his biography of the artist, John McEwen has eloquently told the story of Bellany’s upbringing in Port Seton where his father was first a fisherman and sailor, then a boat builder and also in Eyemouth, another fishing village further down the coast in Berwickshire and his grandparent’s home. There it was not just that he was surrounded by boats and the sea. Port Seton and Eyemouth were no yachting marinas. It was that this world was entirely shaped by the age-old relationship of fishermen to the sea. Still hunters like our most distant ancestors, pitting their skill and courage against the sea’s unpredictable power, hunting the fish they depend on in a relationship even older than that of farmers to the land, theirs was a world of daily, casual courage, of skill and knowledge learnt from experience and collective momory, and too of close kinship. Mutual dependence is vital when the threat of sudden death in the sea’s dark waters is constantly present to be warded off by supersitition, or in the world of Bellany’s childhood accepted in a bleak religion of atonement.

When he enrolled in 1960 at Edinburgh College of Art, though it was only ten miles from his home, Bellany joined an utterly different world, but he embarked immediately on an iconography that drew directly on his upbringing shaped by the sea. As early as 1962 he painted The Boat-Builders, a huge picture of men working in the Port Seton boatyard. It was inspired by Léger’s monumental scenes of the industry, but it rendered his own experience in the language of Léger’s heroic Modernism. This ambitious compound reflected the inspiration that he found in the ideas that were the subject of impassioned conversations in the smoky atmosphere of Milne’s Bar, the Edinburgh pub where Hugh MacDiarmid, leader of the Scots Renaissance poets held court, and which Bellany frequented in company with his friends Alan Bold, a student at Edinburgh University and Sandy Moffat, a fellow student at the college of Art. Twenty-five years before, one member of his circle who particularly befriended young artists, John Tonge, had written The Arts in Scotland, a polemical history of Scottish art. Alan Bold also later edited an unpublished text by MacDiarmid, Aesthetics in Scotland. In both these texts the kind of thinking about art that was current in this Scots Renaissance circle is clearly set out. Passionate and partisan, MacDiarmid’s poetic nationalism was driven by the will to make an art that was rooted in the history and distinctive experience of Scotland, but could take its place internationally in the modern world without apology.

These were ambitions that fitted very closely to the way Bellany’s own experience was already shaping his art. And it was in keeping with the combative spirit of this poetic nationalism that in Edinburgh in the summer of 1964 and again the following year he and Sandy Moffat together stage defiant open-air exhibitions. Bellany’s were social realist pictures of fishermen and the sea. There was an additional note of defiance in this because in them he was turning to such sources of inspiration as Rembrandt, Courbet and Goya and not only for his imagery. He evoked Courbet’s defiance of the establishment directly as the model for his own actions exhibiting this way. In this post-modern era to choose such historic figures as models may seem quite normal but at the time it defied all the accepted conventions of Modernism. It was also a rebellion against the prevailing mood in the College of Art where Willaim Gillies was Principal and where such ‘attitude’ was regarded as a distraction from the serious business of painting.

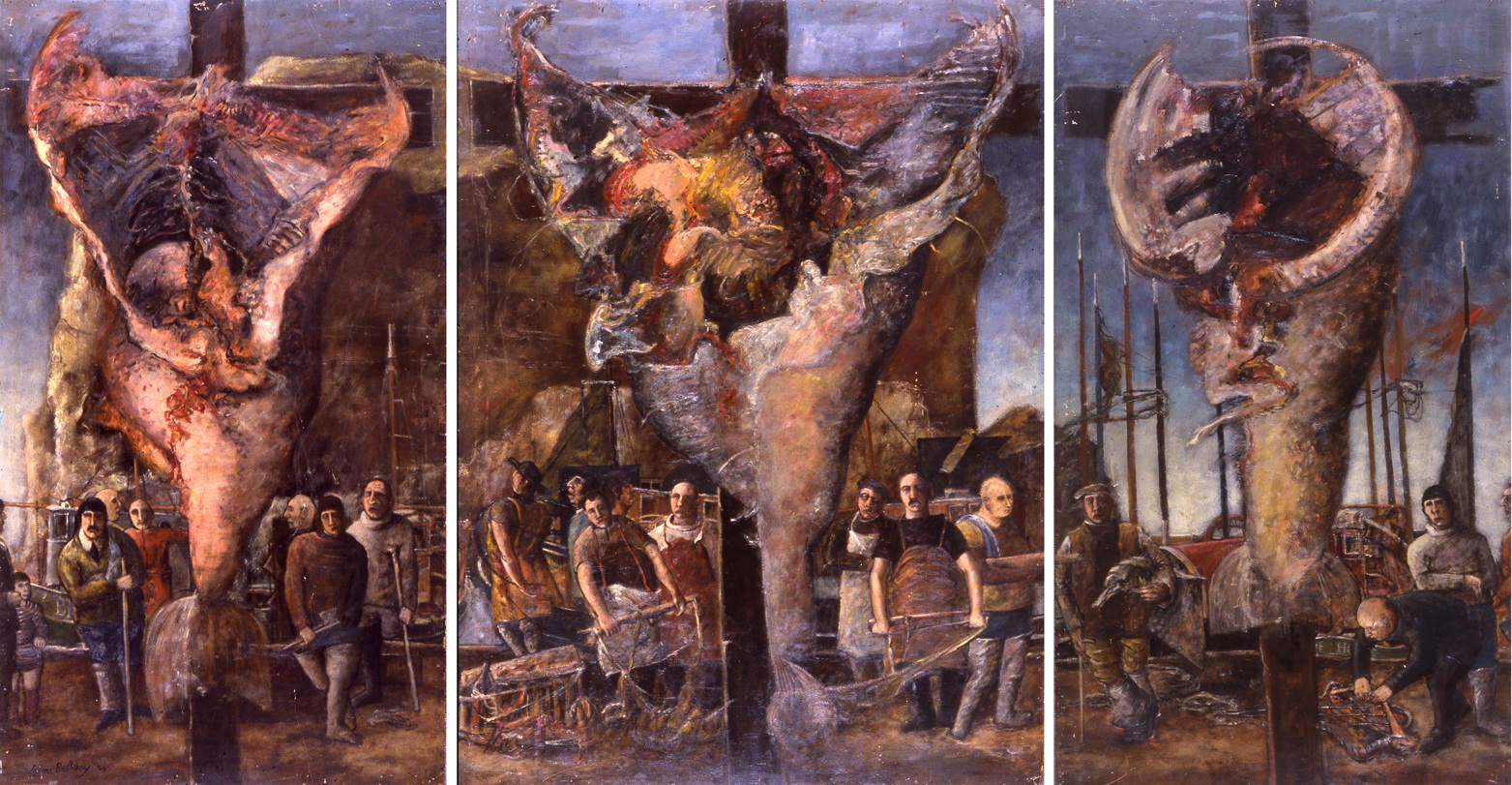

But though some of these pictures were social realist in a straightforward way, others were already strangely haunted, presenting an imagery whose imaginative intensity belongs in the world of the Surrealist exploration of the darker corners of the individual unconscious rather than in any celebration of the simple, collective dignity of labour. For instance in 1964, the year he left Edinburgh to go to the Royal College of Art in London, Bellany painted what is still one of the most grandest and most enigmatic pictures. It is simply called Allegory. It is a huge triptych in the form of a Crucifixion, but instead of Christ and the two thieves, the three crosses carry the bloody carcasses of gigantic, gutted fish. In form and execution these echo Rembrandt’s Flaxed Ox in Glasgow. The fishermen, including the artist are gathered round them like soldiers at the Crucifixion, but they are impassive as though just doing their job. There is fatalism in the way they stand, accepting their role and the inextricable entanglement of life and death equally in the fisherman’s trade and in the great metaphor that is Christianity.

And these are both invoked here. The picture draws on the classic imagery of Western art. The blood-thirsty imagery of guilt, suffering and death that is the common currency of traditional Christianity is part of its history. But the picture locates this in the world of fishing and fishermen where the artist as a child had been exposed to the same imagery from the pulpits of the Plymouth Brethren and the Church of Scotland, and there it was liberally illuminated by the awful glow of Hellfire in a way calculated to strike terror in any child’s heart. But of course too, also invoked here is the whole place of fish and fishing in the New Testament story and the early symbolism of Christianity.

Nevertheless, for all these references, the imagery in the picture is purely intuitive, dependent on subjective associations, not on any deliberate construction of narrative meaning. It has a bearing on this approach that Alan Davie was something of a hero to these young men, and his painting was also typical of the Edinburgh College at the time. Alan Davie himself was a graduate of Edinburgh. Robin Philipson who was head of Painting there when Bellany was a student was a contemporary of Davie and he too stood passionately on this approach. He befriended and encouraged the young artist even as a rebel and in many respects Bellany himself remained loyal to this tradition.

A wonderfully direct and powerful portrait of the artist’s father from this date shows him in working clothes, a cigarette in his mouth, arms tattooed, but leaning on one of his son’s paintings, endorsing the dual identity that the artist gave himself in a self-portrait painted at the same time. This shows the young artist as a hero in the generalised Romantic convention, but it also shows this particular artist as a fisherman. It is perhaps a more boyish version of this self-portrait that looks down on the scene in A Scottish Saturday Night. And the rest of the imagery in the current exhibition shows too, he has never really lost that dual identity.

While he was at the Royal College, for all the pressure of fashion Bellany stuck unflinchingly to his identity and to the convictions about painting that he had formed in Edinburgh. So strong were these and so clearly have they shaped his subsequent art that when in 1968 this graduation from the Royal College was marked by a solo exhibition in the Sculpture Court of the Edinburgh College of Art, it included several pictures that have proved seminal in his later development and which still find echoes here: Kinlochbervie for instance, a row of men gutting fish arranged like the apostles in a Last Supper, a fishing boat behind them, or The Obsession (Whence do we come? Who are we? Whither do we go?), five figures, erect but twisted into tortured poses, starkly ranged against the sea, together but isolated from each other, four of them facing us directly across a table, bloody with fish and guts. They watch us like W.H Auden’s The Witnesses:

In the day and in the night

We are watching you…

We were the whirlpool, we were the reef

We were the formal nightmare, grief

And the unlucky rose.

In a common debt to surrealism there is much in the sinister mood of Auden’s poem that matches the character of all Bellany’s earlier painting. But in these two pictures, as in Allegory, he also uses a quasi-Christian iconography for images of fishing and fishermen. The title of the latter is a quotation from Gauguin. It sums up the sense of the struggle for meaning that gives such power to these pictures. Remembering this struggle it is surely also the same row of haunting figures from painting who watch us again lined up on the distant boats in several of Bellany’s current paintings. But in these later works all this is no more than an echo, a painful memory, still clear, but far enough away on the other side of sorrow to hurt no more.

In 1967, a trip to East Germay, anyway a strange, disturbing destination at that time, included a visit to Buchenwald. Pictures that he painted subsequently, inhabited by figures in the striped pyjamas of the concentration camps, are the most terrifying that he ever painted. Pourquoi? For instance shows three figures brutally dismembered in a manner reminiscent of Goya’s Disasters of War. Their bodies are displayed on three trees as though in a Crucifixion. The composition also recalls directly Grünewald’s Isenheim Altarpiece, but the agony in these pictures is not simply illustration of the horrors of historical fact. It does not diminish them at all to see, along with that agony, the artist’s own internal angst. The truly hellish deeds perpetrated at Buchenwald and in the other camps in the name of perverted, demonic, self-righteousness struck a specially powerful chord with the artist perhaps because he could see in this Nazi evil the same self-righteousness of an elect that was besetting sin of the Calvinist fait in which he had been brought up. Calvinism was the most radical and in many ways the most progressive of all the forms of Protestantism, and so that comparison would b e absurd if it did not also have at its heart an invitation to hypocrisy, and just as Burns had done hilariously in “Holy Willie’s Prayer”, in Confessions of a Justified Sinner, James Hogg explored this, the dark side of this faith. It was about this time that Bellany read this Scottish classic, made famous by André Gide, and he found in it something that he recognised.

But though this helped to objectify and distance one of the most frightening social manifestations of the faith he was brought up in, it was compounded in Bellany’s own private experience by the other side of the Calvinist coin, the unremitting sense of guilt. According to the stern belief whose visions of damnation delivered from the pulpit terrified the young artist and still haunted his adult dreams, born in original sin there is nothing we ourselves can do to redeem the burden it imposes on us. In an etching, The burden, that Bellany made around 1970, this guilt is literally a crushing burden as a man staggers, bowed beneath the weight of a huge fish. This is such a seminal image for the artist that it inspired the photograph taken by Lord Snowdon, and that was used for the back cover of McEwen’s book. In the etching the face of the fish overhangs the man’s, half hiding it like a grotesque animal mask, but he is grinning wickedly, questioning the whole charade. This recalls the second of Goya’s Proverbos, where a wicked face peeps out from beneath a monstrous figure in just the same way. But this sardonic presence is also reminiscent of the Joker in A Scottish Saturday Night and some of the other creatures in these paintings. Like them this fish is also surely a sexual metaphor, however. That of course is in keeping with the story of Adam and Eve and the nature of original sin. And the tension between this sexual guilt and the animal drives that it is invoked to combat and repress, and the way that this is harnessed in marriage is the theme of a whole series of pictures that Bellany began at this time. He reflects in them directly on his own marriage to Helen, whom he married in 1964; and the tensions within it led eventually to divorce.

In another painting also with the title The Obsession this is represented directly in a tormented marriage bed. The man, head in hands, is consumed by guilt. The woman is spread out like an inflatable sex-doll. On the wall above the Crucifixion locates all this in the Christian vision of necessary suffering. It is something very like this Crucifixion that appears here on the wall in the Vision of the Bride, making another link, though she and the other wanton brides in these recent paintings belong to an altogether happier dispensation. In their almost cheerful sexiness, it seems these tensions are now resolved.

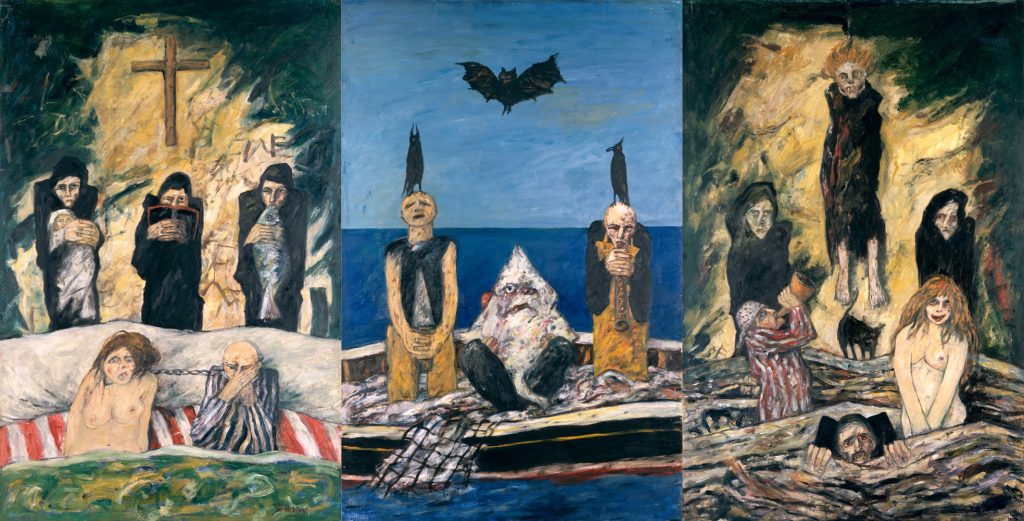

But in a painting like the triptych Homage to John Knox painted in 1969 this Protestant inheritance is excoriated directly in the ironic invocation of John Knox, the founding father of Scottish Calvinism. In the left-hand panel, husband and wife are literally chained together in a marriage bed watched over by three grim figures. In the right-hand panel, this has turned into a vision of Hell itself. In the central panel two fishermen stand against a blue horizon in a boat full of fish, drawing in their net. In spite of this success, of this bounty, they are emaciated and despairing. A bat hovers above them. A grotesque skate is between them. Blackbirds of guilt sit on their heads.

Hitherto Bellany had been content to use people and things in a direct way. However emphatically he described them, they remain recognisably themselves. But in this central panel a new surreal element is apparent. People share their world and at times to there very identity with birds and fish and dogs and other increasingly strange creatures. Sometimes these could be masks. At other times they are metamorphic: men with bird’s heads, women with fishes’ bodies, dogs that become birds or monkeys, their identities intermingled: tragic – though also sometimes comic – creatures that step straight out of the unconscious. Max Beckmann whose work Bellany saw in his major retrospective in London in 1965 was an influence here in turning him towards this surreal imagery. The central panel of Beckmann’s great triptych Departure with strange, emblematic figures standing in a boat against the sea that in turn derive from Raphael chimed so closely with Bellany’s own vision that he made his own. Echoes of it are still strongly present in the current exhibition.

But though these metamorphic creatures – the skate, the dog-faced baboon, the death’s head, and many others – recur in Bellany’s painting from this time forward, – here in Valhalla, for instance, two of them appear without human companions – they stand collectively for many things: guilt, the animal urges that will not submit to its blackmail, fear of death, the necessary brutality that links humanity to all the other creatures that must kill to live, and all the rest. But they never surrender to fixed meaning. They are truly metamorphic, changing their shape and their meaning constantly.

They belong in the subconscious world from which they emerge, beckoning us to follow as they disappear again into its shadows.

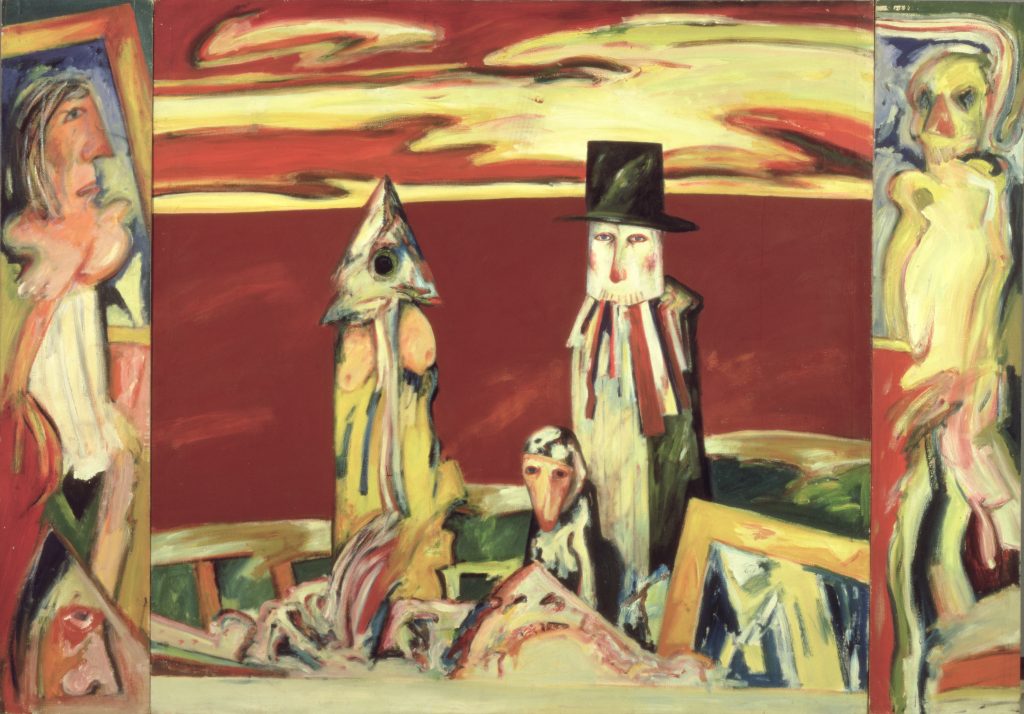

In the nineteen seventies this kind of imagery cam increasingly to dominate his art. A key picture here is the triptych The Sea People from 1975. Three strange creatures stand against the sea. Two are half-human. One seems to be a woman with a skate’s head, the other a man with a death’s head and a top hat. A dog-like creature stands between them. This broad central panel is flanked by two that are tall and narrow. Each frames a figure in a coffin-like space and one is distinctly corpselike. But the other seems to be a woman in a corset who may or may not be in a picture in a frame half visible behind her.

Not just this figure and the framing device, the top hat and many other aspects of this painting recur in pictures in the current exhibition. Even the composition of the central panel with two figures against the sea recurs in A Boat called Maria. But that very compassion illuminates what has happened. The recent picture is light in colour, elegiac in mood. In The Sea People, the colour is harsh and insistent. The sea is blood-red. The boat set against it is dark green. The Sky is lurid red and orange.

Everything in the picture is sinister and disturbing. But if there is little comfort here, the artist still had much to go through before he emerged into the sunlight of his recent paintings. In 1978 he was divorced from Helen. He and Helen were later remarried, but in 1979 he married his second wife, Juliet. But in 1985 after a harrowing illness she died, and his father died in the same year. In 1987 he thought that he too would die when drink, an integral part of culture of the Scottish circles in which he had come of age, finally destroyed his liver and no transplant seemed to be available. In 1988 however his life was indeed saved by a transplant.

From the terrifying intensity of The Sea People, over the next decade his painting became more and more directly expressionistic, violent in execution, not just in imagery. Take If Music be the Food of Love, Play On, for instance, painted in 1983. It is a diptych and in the right-hand panel, though they are roughly brought together, there are recognisable bits of keyboard, a strange bird a jug and a blue horizon, if rather a tilted one. Music has always been part of his life. When he was young he played the piano in a band called The Blue Bonnets so the keyboards here are a link between that early experience and the paintings on view here where the musical themes appear again. But in the left-hand panel things are only suggested, not described. Mostly they seem to be purely abstract: forms shaped by a brush driven by an expressive need too urgent to pause over details, but by their very abstraction also suggesting a different, more direct analogy with music.

But here personal need and artistic logic coincided as they have always done with Bellany’s painting. The dark mood of his earlier work found focus in an iconography rooted in the outside world, but is was already harnessed to an inner expressive need. That is what gave it its power. In a picture like The Sea People the demons that haunted that early work are represented directly. But they could not simply be pinned down, labelled and dismissed like specimens in an entomologist’s collection. They have an elusive life of their own and it is that which is pursued in the desperate, restless energy of Bellany’s expressionist paintings of the late seventies and eighties, an expressionism that brought him close to Alan Davie or de Kooning, but from which eventually he turned back as it took him to the edge of incoherence. And he did so when his life itself seemed to be about to be overwhelmed by that same incoherence, but was saved by the transplant in 1988.

That operation was commemorated directly in an extraordinary series of works, outstanding among them a set of etched self-portraits of the artist in his hospital bed, still with the tubes of his life support system in his nose. Immediately before, sick and contemplating his prospect of his death, he had produced another remarkable series of etchings illustrating Hemingway’s The Old Man of the Sea. In this series he clearly identified himself with the old man whose greatest prize was reduced to a worthless skeleton in spite of all his lonely trails and suffering. The etching of the old man alone on the sea with the skeleton of his great fish lashed to his boat seems to be yet another extraordinary, emblematic self portrait.

Nevertheless though Bellany’s art is always intensely personal, you cannot simply ‘explain’ it by reference to his biography. It has it own logic. What is remarkable is the symbiosis between these two things. How his art and his sometimes deeply troubled life have evolved together like on of those strange partnerships in nature where two utterly different species co-operate and by so doing confound their enemies and outreach their rivals.

In the years after his life-saving operation, Bellany’s painting eventually grew calmer and more reflective as his life entered calmer waters. But this change happened gradually. In pictures like The Storm of 1991, Charon’s Boat, or Danse Macabre both of 1993, he is clearly looking back at his close passage with death. Wild and troubled feeling still vibrates in them. One of the greatest paintings of these years, Bounteous Sea also of 1993 sums it up. Once again it is a triptych, but the mood changes between the side panels and central panel. In the left-hand side panel, painted roughly and in sharp and clashing reds and greens, a grotesque figure thrusts his lecherous attentions on a girl in a state of undress. She looks up, suffering his attentions with resignation. In the right-hand panel, there is a salient death’s head and what seems to be a portrait of the artist, but half-obliterated by the violence of the execution and again in green and orange.

But in the central panel, though this colour key continues and the handling is in part rough, these discords, visual and psychological, are resolved by the blue sea. The horizon line is clear and simple, dark blue against light blue sky. Against it the two dominant figures face other calmly. One is a girl with naked breasts and the other a phallic toucan. Though so oddly paired, they seem to ease in each other’s company and have a strange and touching dignity. In the end it is the bounteous sea that gives back life and resolves discord.

The works in the present exhibition have evolved from this vision. We are there as witness, not just of the exhibition, but the whole story that it tells, one in which now, transmuted into art, we can recognise that we share. But there is in these pictures too, a new and reconciliation; that the ghosts that haunt memory and the creatures of imagination no longer bringing conflict to the conscious mind, but beginning to be at peace with it. Emotion recollected in tranquillity, the noble ridge of the Cuillins ‘rising on the other side of sorrow’: the very stuff of poetry.

Duncan Macmillan

Duncan Macmillan is a Professor Emeritus of the History of Scottish Art and formely Curator of the Talbot Rice Gallery in the University of Edinburgh. He is also art critic of The Scotsman and has written widely on Scottish art both historical and contemporary. Among several books, his major work Scottish Art 1460-1990 (published by Mainstream and reissued in 2000 as Scottish Art 1460-2000) was Scottish book of the Year for 19990 and is the standard text on the subject.

| Exclude FooBox from this page or post? By default, FooBox will be included. |

55 blocks

5709 words

Notifications

55 blocks selected.